These days too many media outlets seem to go for sensationalism rather than facts, but not usually PBS. I watch their news hour every night and expect it to have thoughtful, in depth reporting, unlike the sound bites from many other news shows.

Thursday night’s piece on the privacy issues from DNA testing was a travesty. This misleading headline on their web site about that segment is not what I have come to expect from PBS – “Genetic genealogy can help solve cold cases. It can also accuse the wrong person.”

No, genetic genealogy does not put the wrong people behind bars. Autosomal DNA is just a very accurate tip that points police to a person or family. In order to make an arrest they next collect the suspect’s DNA from discarded items to see if it is a match to the crime scene DNA. It is those results they take to court, not the genetic genealogy theory.

The wrong person accused scenario that they refer to happened several years ago from using Y DNA, not the full autosomal DNA currently used by genetic genealogists. PBS interviewed Michael Usry about his experience of being suspected of a horrific murder because his Y matched the crime scene and even he suggested that it was not such a bad thing to catch murderers and rapists by using the DNA of their cousins. Click here for an article from 2015 about the Michael Usry case that explains what happened back then.

Note that the Y is only one of 46 chromosomes (in 23 pairs but Y pairs with X) and it is the only one which changes extremely slowly. Therefore can reach back many hundreds of years. For example I have a cousin who has a perfect Y match with a 5th cousin where their common ancestor lived in the 1600s. So clearly, the Y is just not useful for law enforcement searches.

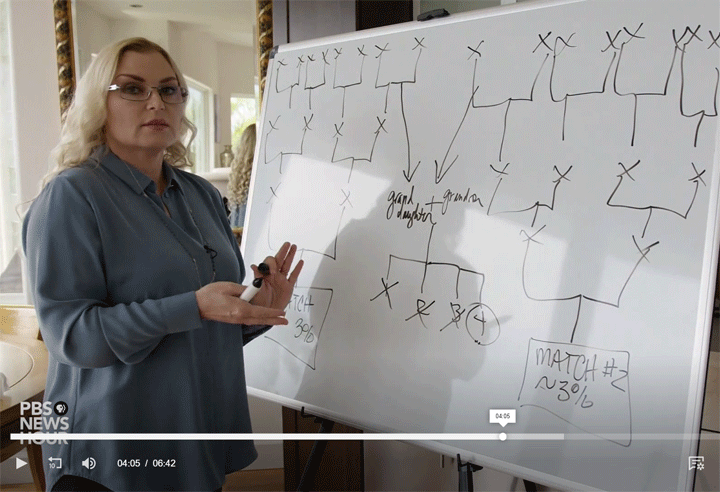

CeCe Moore explaining how autosomal DNA led to a killer – screenshot from PBS News Hour Wednesday Nov 6

Wednesday night’s episode (click here) did a wonderful job of explaining how autosomal DNA is used to solve cold cases. PBS interviewed both famous genetic genealogist Cece Moore and Curtis Rogers, the founder of GEDmatch. I even made my husband watch it so he could better understand what I do when I help people with their DNA results. He enjoyed it.

So I was expecting Thursday’s follow up episode on genetic privacy to explain to me why so many people are worried about this issue. Personally if any of my cousins are violent criminals I am happy to out them, but I get that people did not expect this use when they uploaded to genealogy sites, so their permission is needed.

Instead Thursday’s show was highly inaccurate. So I wrote this blog post… will I cancel my PBS membership? We will see.

UPDATE 8-Nov-2019: A number of readers have pointed out the glaring innacuracy of the November 7 episode claiming “that Brian Dripps had been convicted of killing Angie Dodge and is serving a life sentence” when in fact the case has not even gone to trial yet. Although he confessed, he is now pleading not guilty. A recent non-sensationalist summary of that case is here: https://www.ishinews.com/events/unraveling-the-twisted-case-of-angie-dodge/

UPDATE 9-Nov-2019: The PBS NewsHour has corrected the Brian Dripps statement in November 7 episode on their website and also retracted the incorrect information towards the end of their November 8 episode.

I hope to write to PBS and explain – maybe they will ‘correct’

EDIT – I meant I hope YOU write to PBS or send a link to this blog post.

Kitty, thank you for providing this information. I have shared it to the Facebook pages of my local genealogical societies. As professional genetic genealogists, we have to take the lead to educate our clients and other genealogists about the use of DNA in these cases.

It’s The News Hour, not PBS as a whole, that is at fault. I agree it’s a really bad error, but please don’t cancel your subscription.

Thank you for contacting PBS about the inaccurate reporting. They should have checked their facts with several of the well-respected genetic genealogists, including yourself, before airing their story.

Once they have arrested a suspect, LE can get a court order to get the suspects DNA. This DNA, taken directly from the suspect, with witnesses, is then compared to the crime scene DNA and used in court. I don’t believe any of the genealogy or discarded artifact DNA is used in court – they were just steps to narrow down the suspects.

I was also disappointed. The use of yDNA in the false arrest should have been stressed. The difference between atDNA and yDNA testing as they focused on Gedmatch would have made the false arrest clearer.

I missed both of these segments although I usually watch NewsHour. As someone concerned about the privacy issue — and regularly encountering pushback about testing from close relatives — I would want to hear an edifying debate about the 4th Amendment, what constitutes “probable cause”, can these dna databases be opened for “fishing expeditions” (or not) etc. The real “meat” (to my mind) rather than superficial pablum and click-bait stuff.

Afternoon,

Nsikan Akpan here, science producer on both segments and the writer of the digital piece in question. Happy to politely chat about our stories.

Re autosomal genealogy

The pitfalls of autosomal genealogy were raised to us by genealogist CeCe Moore in her interview and backed by statements from Benjamin Berkman, deputy director of bioethics core at the National Human Genome Research Institute, who heads the core’s section on the ethics of genetics and emerging technologies.

As stated in the third section of this digital piece, autosomal genealogy cannot distinguish between siblings — because their DNA is too similar. This can lead to surveillance of family members who have not committed a crime. As also stated in the digital piece, Moore said she warns law enforcement about this pitfall and how it can be exacerbated by the incomplete nature of public records. Moreover, we didn’t use this following bite from her interview in our stories, but she said that she has encountered a case where she “narrowed it down to one family and it’s not any of those people in the family.”

Moore then emphasized, as reflected in the digital piece, that overcoming these pitfalls comes down to being an experienced genetic genealogist (which Moore is) and to law enforcement procedures obeying the highest standards with this forensic tool. The technical aspects of those investigation procedures and standards for DNA forensics, including for genetic genealogy, are not typically made public. Berkman said from an ethical perspective, he would want to see them made public.

Moreover, autosomal genotyping is not foolproof and is less accurate when picking out distant cousins in ancestry matching, as stated in the digital piece.

All that said, autosomal genealogy is just a tip or lead (as we state), but it can also lead to surveillance of innocent people, which could present a risk especially in unexperienced hands.

Re Michael Usry and Y-DNA gene

Thursday’s broadcast segment and the digital piece (especially the digital piece) explain that Usry’s case did not involve autosomal genealogy.

Moreover, Usry himself mentioned that he supports new tools for forensics despite his experience, but that he is still worried about the privacy issues. The broadcast segment and digital story go into how those privacy issues appear through public access of public DNA databases.

Moreover, the broadcast segment and the digital story express the debate about the balance between individual privacy and community security. For example, there are multiple quotes in the digital story that speak to this issue, including one from Berkman:

“If we’re weighing convicting someone who’s committed a terrible crime against the idea that an innocent person might have to give a blood sample, that seems like a trade-off that most people would be willing to make.”

Re Brian Dripps

We have published a correction on the segment, clarifying that Dripps has not been convicted, but rather charged and given a confession, according to investigators. This correction will also air on the show.

I forgot to correct what you said about autosomal DNA and siblings … of course autosomal DNA can tell siblings apart (unless they are identical twins) because they inherited different pieces of DNA from their parents.

What you wanted to say,I presume, is that the methodology leading to a specific family via matching autosomal DNA in the databases cannot tell which sibling it is. Another reason genetic genealogy is just a tip from which further police work muct be done.

Thank you very much Nsikan for your thoughtful and careful response. It is good to hear that you are correcting the information on Brian Dripps.

My concern is that the headline and tone of that 2nd segment are pandering to people’s fears about DNA testing. The distinction between the use of Y in those early efforts and today’s autosomal familial approach could have been made clearer. The concept that we all leave our DNA everywhere and it is like a giant fingerprint was never mentioned.

Yes using family DNA matches is just a tip which would lead to surveillance hoping for a discarded item having DNA that matches the crime scene on it. Again, this was not made clear in the video clip.

The published piece on your website is far clearer.

I do love the NewsHour and was very distressed by what I perceived as misleading sensationalism in the 2nd piece. I was hoping for deeper discourse on the real issues of privacy and DNA. While I am happy to out criminals in my family, what about the possible abuse down the line? At least I think that is what concerns other genetic genealogists, …

No problem at all, Kitty. I am always open for a discussion. I can guarantee that NewsHour was not attempting to be misleading nor sensational. The second segment is mainly pointing out the potential pitfalls of storing DNA profiles in databases, which is highlighted not only by our segment but by this week’s story in The New York Times about the GEDMatch search warrant. Moreover, I think any piece of emerging technology will raise debates about the pros and cons of its use.

P.S. To tack onto your last point about misuse: During our reporting, I wondered about a scenario wherein a suspect identified by autosomal genealogy is deceased and the body can’t be exhumed to confirm a direct DNA match.

Nsikan –

The first segment you did was so very powerful and well done that the second segment was a disappointment. I am happy you corrected the part about Brian Dripps online, in the Nov 8 News Hour, and in the video currently posted.

I was perturbed by your use of the old Usry case and calling it an “early form” of DNA testing when it was Y DNA, which as I explain in my post, is not feasible to use for identifying individuals. Your new headline “A father took an at-home DNA test. His son was then falsely accused of murder” is still pretty sensationlistic, but then so is the title of this post!

I was hoping for a more in depth exploration of why people are worried about DNA privacy, since I really don’t get that myself. I am used to high standards for your reporting and perhaps expected too much from you all.

Nsikan –

To answer your question about exhumations, this does not seem so terrible to me.

I think the concern is the “Big Brother” worry that DNA can identify you for minor crimes or the GATTACA worry that your short life genes will make you unemployable. Or perhaps you would not marry someone if you knew they carried various bad genes? Orthodox jews have already used this technique to almost eliminate Tay-Sachs and a few other genetic diseases.

Exhumation has been done in paternity cases where inheritance is involved, for example Salvador Dali as reported by NPR.

In criminal cases the deceased was often imprisoned, so a sample of his DNA is usually available. As in the famous Lisa case solved by Barbara Rae-Venter and her team as reported by the Boston Globe.

I think it should be made very clear that genealogical DNA is being used to develop a pool of possible suspects – sort of like a police line-up. Here in Northern Virginia a few years ago we had a sniper who killed a number of folks. Someone saw a white van. Maybe every white van in the VA-DC-MD area was considered suspect, and many were pulled over and searched (and in the end, the sniper hadn’t used a white van). In the end a suspect’s own DNA can be compared to the crime scene DNA (like fingerprints) – the genealogy DNA does not have a “chain of custody” and is not used as proof, just a way to try to narrow down a list of suspects. I get the privacy issues, and wish we had a fairly comprehensive protocol for everyone to understand and follow. As a life-long genealogist of 45 years, I really like the DNA tool. Sensational headlines sadden me.

Here is the Nov 7 episode: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-father-took-an-at-home-dna-test-his-son-was-falsely-accused-of-murder

Thanks Teri!

“These days?” It was always thus.

Nsikan –

While I appreciate your desire to discuss the issues raised by Kitty and others, your responses have left me with the impression they were made more in a spirit of defense rather than of discussion.

I did not detect even a hint of an axe being ground in her posts. To the contrary, while criticizing this single show, she was quick to balance that criticism with her personal testimony of the high journalistic standards she had grown accustomed to from PBS. For myself, I noticed a slip in these standards after the passing of the highly regarded, even beloved, co-anchor of “The PBS NEWSHOUR”, Gwen Ifill.

Regarding the discussion about this episode, perhaps starting with some degree of acknowledgement would allow it to bear fruit.