One of the benefits of doing genealogy is seeing history through the eyes of your ancestors. Sometimes helping another with their family history has a similar advantage. Cathie’s father wrote up his experiences in the 30s for her. I was so charmed by them that I asked for permission to publish a slightly edited and condensed version on my blog. Here it is:

I left home when I was just 16 in June of 1929. I worked on a farm, a golf course and spent the winter in a home for homeless boys in Chicago until clement weather arrived.

I then “rode the rails” with a vengeance when real Spring weather arrived — April or May 1930. I had made up my mind I wanted to reach the West Coast to become an apprentice seaman and, (for some obscure reason), to reach Japan.

Let me digress here a moment. Hitchhiking was the optimum way of traveling for a “wanderer” (later, a “bum”) in densely-populated areas. One could get to the outskirts of a town or city easily and there was considerable traffic from whom rides could be cadged with the thumb. But when it came to crossing the vast distances of the West, freight trains were the only answer. (You could starve to death hitchhiking in say, Wyoming or Nevada.)

So I took up “riding the rails”. It was not easy. You had to find the freight yards, seek out other bums who were going to take the next west-bound freight to assure yourself you had the right train and then position yourself strategically between where the train was made up, beyond where the railroad “dicks” kept the train under surveillance but still close enough to its point of origin before it reached dangerous speed. Then jumping into an empty car was no simple task. The outside door latch had to be unfastened, the door pushed open; then you used both your arms to lift yourself so you could slide on your stomach into the car. If your travelling companions had already gotten into the cars, they would give you a hand thus making the entry in a lot easier.

One had to be prepared for the monotony of hours, or days of travel. The scenery was generally entrancing. Freight trains stopped a lot, as you could dismount and stretch your legs or seek out a drinking water source. The brakemen riding in the caboose knew they had unauthorized passengers but normally took no adverse action against them. Chasing bums off trains “was not their job” (they left that to the railroad dicks).

Anyway, I finally reached Oakland, California and upon inquiry, found that the port from which ships left for the Orient was Long Beach, just outside Los Angeles. I hitchhiked down there pronto and got my name down on the hiring hall list as being available for trips to the Orient as an “apprentice seaman”. Then I waited, and waited and waited — for days, then several weeks on end. I finally got talking to someone who was waiting in the same hiring hall and seemed to want to talk. He was an “able-bodied seaman” but was quite willing to hire out — at lesser pay, of course — as an “apprentice,” and I asked him how many experienced seamen like him were also willing to take a lower paying job. He turned around, waved his hand at all the guys sitting around, waiting for a call, and said, “Take your pick.” My density finally having been penetrated, I knew I was not going to be hired as an “apprentice,” so long as there were scores of “able-bodies” willing to work for less.

So I no longer waited at the marine hiring-hall, knowing this was useless. I also got the first smell of the rapidly expanding unemployment situation. This had already developed in the few short months from the stock market crash in October 1929 to the Spring 1930.

Then came an episode, the largely pleasant memory of which still lingers with me to the present day. I left Long Beach profoundly depressed knowing that my “maritime” ambitions were forever doomed. I hitchhiked up the California coast, not then appreciating its beauty in my welter of gloom.

Landing in Oregon, I was just in time for apple/pear-or-whatever picking time. After working perhaps two days at the most, I finally had to admit to myself that I was frightened to the core. At that time, the growers still used the tall apple/pear/peach trees to grow fruit. The present low fruit trees which can be picked with the aid of an eight or ten foot ladder had not yet been developed. Accordingly, they had to use 20-25 foot ladders to pick their fruit. At first, 1 thought I was merely being cautious in picking the fruit but then I became honest with myself and realized I was scared to the core. These ladders brought out my inborn fear of heights as nothing else ever had. Of course, I could trot along the roof of a moving boxcar but this was different.

I collected my money and left. It then occurred to me that I was not too far from Yellowstone National park and also that the staff might need summer help to assist in the housekeeping (I never made it to Yellowstone at that time). I continued then to hitchhike through Idaho.

At some point before reaching Pocatello, I was picked up by a local rancher, a young man, who (of all things) asked me jf I were interested in working for him. I could scarcely believe my ears, but I said “yes” without sounding too eager. He said he needed help on a fence he had started on a homestead he had tentatively acquired from the United States Government. Apparently, the permanent acquisition of a homestead was conditional on making so much in expenditures for I believe five years.

Next morning, bright and early, my employer and several other men assembled a substantial line of wagons and horses and we took off to the homestead in the mountains. The going was rough. The road, if you could call it that, was barely discernible as such in many places. It led upward consistently. When we arrived at the homestead, I then discerned my employer’s occupation. He was a sheep rancher. There were several hundred of his animals there in the area, in the care of a Basque herder.

The purpose of our being there was to shear the sheep. They constructed a rack from which was hung a long narrow bag to hold the sheared wool. My role in this particular exercise was to get into the bag and trample down each glob of wool as it was tossed in. By the end of the day I smelled more like a sheep than any of the flock. I bathed in an icy stream which ran near the cabin, which he, the owner, had there.

This sheep-shearing continued for several days as I recall, until all the mature sheep were naked as jaybirds. The bags were then loaded on a long wagon, which was left with me, and the entire crew went back to the valley.

I was left there quite alone with a cabin to sleep in, two mules to ride when I felt like it and enough food for several weeks. My role was to place a post every eight feet in a designated line. The pay I was to receive was to constitute part of the expenditure the owner had to make his title to the homestead irrevocable.

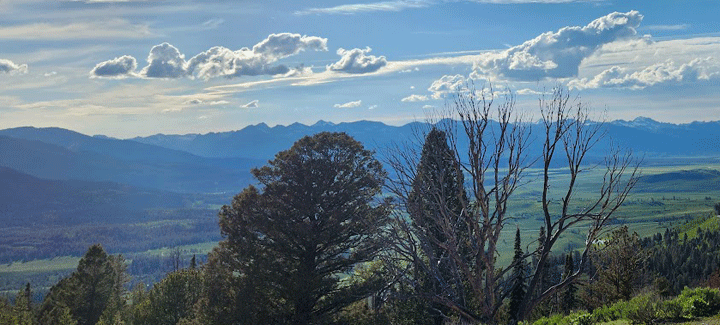

The country and the view from the plot of ground was magnificent. I have since that era been to Europe and have seen even the Swiss and Bavarian Alps but little that compared with the Idaho Rockies. I stayed there several months. My employer would show up every few weeks to replenish my food supply and to see how things were going, particularly to assure that the posts were being emplaced along the correct designated line.

My mules each had a hobble strap which I affixed each evening before dark on their front feet so that they could not stray too far from the camp. This gave me some trouble at first but I quickly acquired the knack and it became a simple chore. They were great riding animals.

My only complaint concerning the situation were the porcupines. The owner had left numerous bags of salt (for the sheep) in front of the cabin. At night when I was trying to get to sleep, they would gnaw at the floor boards to try to get the salt. This kept me awake so I would get up with a stick to beat them off. I did hit one on the nose once, killing it and then felt like a murderer.

I completed the job after several months, so I rode along a wagon loaded with the bags of sheep pelts (they apparently were left there in the mountains to dry out) back to the valley. My employer was apparently pleased with my performance and said something to that effect.

The next day was the day of reckoning and payment. They figured up how much they owed me, then announced that one of the family member was going to town and would purchase for me anything I wanted. Among other things, I asked for several tins of Prince Albert tobacco and some cigarette papers, as, by this time I was quite adept at rolling my own. The family member came back and had everything I asked for except the tobacco and cigarette papers. When I asked the proprietor of the spread why these items had been omitted, he said he did not approve of smoking […] and could not have it on his farm.

I was speechless for a moment or two and then said that in this event, I would take my money and leave. [… omitted …] When he finally simmered down and returned, he finally gave me money — only half of what I had coming.

I was, of course, upset at the time but could do nothing. I walked off with what he chose to give me (about half) and slept in some barn (it was dark by this time) along the way. When I sought out the sheriff in the next town and complained, he said, quite politely he could do nothing. It was my word against my ex-employer and, of course he could not take sides […]

I was quite upset about this at the time but, upon reflection, I think I got the better of the deal. The cash he withheld fades into insignificance but I will always treasure the several months in the Idaho mountains. It gave me a real sense of the worth of life at a time I began to think it had none.

But other than this remarkable interlude, the rest of my time on the road was grey and depressing. I managed somehow to visit, in a “travel” status, 45 out of 48 states of the union at that time, both by freight trains and hitchhiking. I cannot dredge up from memory any outstanding or remarkable events in this three year period.

I had many temporary jobs during this period, interspersed with uneventful periods of idleness merely wandering from place to place, without plan or purpose, on the strength of rumors that there was work to be had at such-and-such location.

Among the jobs I have had were:

- Dishwashing – Fort Wayne, Indiana and Lancaster; Pennsylvania stand out because they each lasted some time, although there were several other places.

- Helping a delicatessen store owner, who had experienced a fire, remove scorching from the boards of his regular place of business, while he continues to operate in a temporary location.

- Picking tomatoes in upstate New York State at some almost unbelievable low prices per bushel.

- Farming – I worked for several months on a dairy in the Catskill area of New York. I enjoyed the work but the owner, a large brute, gradually became more and more abusive and I left before the abuse became physical. At 5’8″ and 140 pounds, I was no match.

- Handyman at a dormitory of a ladies college somewhere in upstate New York. I worked hard but left because I could not seem to persuade any member of the ruling group to pay me the agreed periodic wage.

Finally [ed: in about 1935], I read in the paper where Franklin Roosevelt came out with a program whereby jobs would be provided for anyone who wanted to work. I happened to be in Augusta, Maine when this program was announced. I sought out the individual who was in charge of the program[…] and was immediately put to work setting up a room to store all the blank forms that were part of the program. I must have impressed Charles Brown with my industry, for in a few weeks, I was given a job in the payroll department for that program state-wide.

Anyway, to shorten this, in about a year and a half, I found myself going to the Bentley School of Accounting in Boston. This led to a tax accounting position with General Electric Company in the former main office at Schenectady, New York.

Then after five years with General Electric, I was drafted but wound up commissioned and stationed in England, then Germany (after 1945) and finally found my “true calling”, a United States Government employee…

Thank you Cathie for sharing this!

illustrating photos from Kitty Cooper’s own travels

I loved reading the story! Thank you so much for sharing!

Thank you for sharing this unique snapshot of life. I have some journals written by various family members in periods of the 1800s and early 1900s. I treasure “hearing it in their voice”. Please tell Cathie how much pleasure she gave by sharing her family.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your well written family history. Thanks for sharing. How lucky anyone would be to have such a great story left to them. I’m jealous.

Jerry

Fascinating read, Kitty. Thank you so much.

One of my mother’s brothers “rode the rails” and mom used to tell some of his stories. My uncle was born in 1911 so would have been about this same age. I don’t think anyone ever documented my uncle’s stories so reading this gave me an idea about his life. This is a great read, thank you.

This was a memorable read. Thank you so much! I have one ancestor, my maternal grandfather, who was a railroad engineer in Washington State, back in those days.

Also I have an ancillary relative who was apparently killed while riding the rails during that same period.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Oh, my! What a story! One great uncle rode the rails during the Depression, so the details about that are so welcome. Right before my husband was sent to Vietnam, he was stationed at Mountain Home AFB, Idaho. We spent time in the Idaho mountains and encountered Basque sheepherders. How I enjoyed the story of those days. I’m so thankful you shared this!

This makes me realize that I should not burn all my diaries and journals I kept when I was a young woman. They would be a fairly accurate picture of life in the 1960s and 1970s! So glad that you shared this true-life story!

What a great slice of life in the 1930’s. I also had a restless uncle who tried riding the rails before settling down.